Unemployment at a staggering 12.6%.

A lawless American government.

American domestic spying approaching the same level as the old USSR.

Foreign enemies with nukes on the move.

And more. Lots more.

Can you see why I might be in such a pessimistic mood?

My mood, of course, feeds my gaming. And being in such a cynical state of mind, I just haven't had the disposition to pick up Titanfall, the game whose beta so made me gush just a few weeks ago. The idea of playing a game that takes place in a clean, high tech type of future - if war torn - just isn't doing it for me. I desire something more reflective of my dispirited temper.

So, what does one play when he is downright dour? Well, I suppose that depends on the player. For me, though, it always comes down to two games: S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, or Fallout 3. I am going to discuss the former today.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl is a 2007 game from the now sadly defunct GSC Game World, one that is loosely based on the award-winning novella, Roadside Picnic.

In the ongoing debate as to whether a video game can be art, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: SoC is one of those titles that can serve as prima facie evidence in the affirmative. Like the fantastic Soviet movie of the same name (also predicated upon Roadside Picnic), S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is a game that, while it does have monsters and shoot-outs, its real horror is found in the sense of despair and abandonment that seeps from every pore of the Zone. It is the pixelated version of Edvard Munch's The Scream.

This is what separates S.T.A.L.K.E.R. from it's Americanized cousin, Fallout 3. While Fallout portrays a world devastated by all out nuclear war, it is, nonetheless, a world where people still struggle to build a society amidst the ashes. Sure, their buildings might have been reduced to rubble, but darn it!, they are not going to leave without a fight. In a sense, there is a thread of optimism to be found in Fallout 3, even if it is a very slender one at that. S.T.A.L.K.E.R., on the other hand, offers no such hope. Like the real world Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is a game about inexorable surrender.

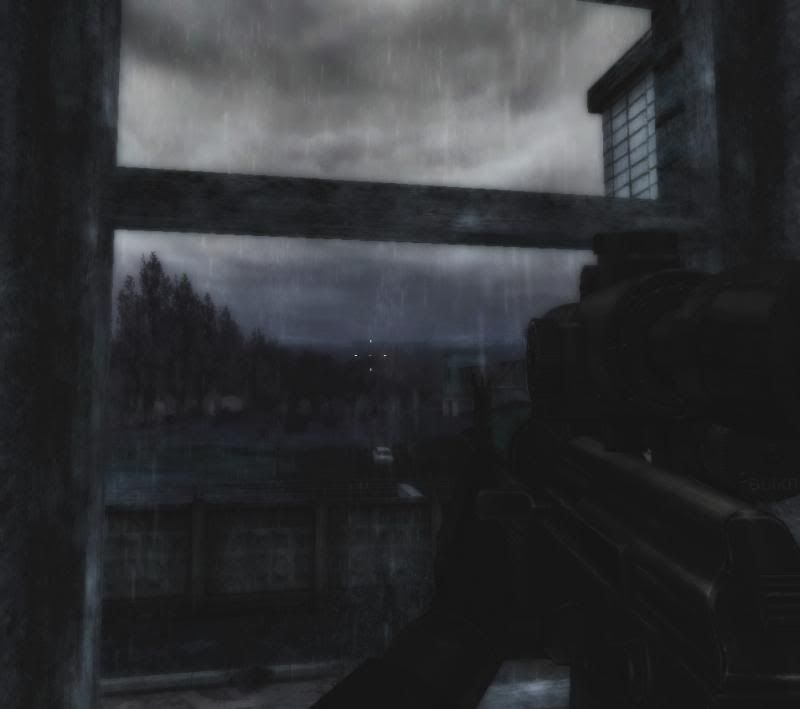

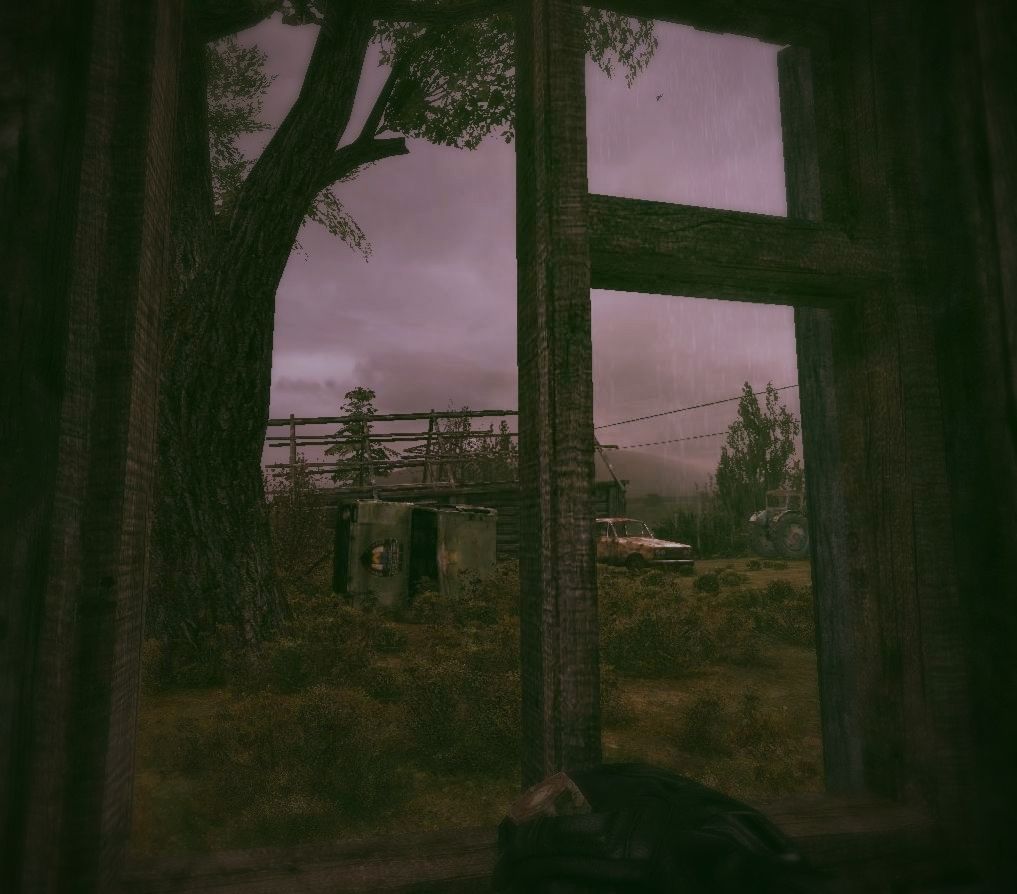

Unlike the plucky Americans of Fallout 3 who refuse to abandon the Capitol Wasteland to mutants and raiders, the denizens of the Zone had no such option. They were forced to drop everything in place and just leave with their lives (a poignant reminder of the real world Chernobyl disaster). As such, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is filled with scenes of hopelessness: deserted factories with heavy equipment left to rust in place; cold, lifeless homes with dark windows and overgrown yards; and civilian cars and trucks parked haphazardly and abandoned, paint left to fade and flake in the harsh Zone environment. It is now little more than an enduring memorial comprised of sad, rotting tokens of a happier time. It is a modern Pompeii, but one more fitting for an age of cold, inhuman super science.

In a sense, the entire Zone has also become one large, haunted house: a place devoid of warmth, and only populated with the ghosts of things that might have been. Even the weather plays into this theme with near constant stormy skies, something that befits a haunted house, after all. The gamer gets the sense that it is almost as if the heavens themselves willfully seek to wash away the abandoned detritus of mankind, all in a futile attempt to erase this painful reminder of what once was.

|

| And Jesus wept.... |

The Zone is, pure and simple, failure writ large. It is today's Detroit....

...and perhaps tomorrow's America? Like Detroit, a once productive and prosperous center of American craftsmanship, the Zone is a warning that the future is not preordained to be golden; utopia is not always just around the corner. Rather, the future can be filled with disappointment and even despair, especially if we, the caretakers of what is and what will be, fail in our responsibilities to shepherd our society along the right paths. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.'s Zone is a warning to all mankind that we are not above the immutable laws of cause and effect. As we sow, so shall we reap.

This is why I find S.T.A.L.K.E.R. to be a powerful warning about the perilous road that America, and the world, is heedlessly trotting down. With perhaps the exception of the most willful optimist, I don't think anyone can gaze at the 20th Century, and what is shaping up to be in the 21st, and express anything other than grave concern. Our course remains unchanged. High technology is wielded with all the carelessness of a child with an assault rifle, and we forget Buckminster Fuller's warning that "those who play with the Devil’s toys will be brought by degrees to wield his sword.”

Speaking about playing with the Devil's toys, there is another powerful cautionary tale embedded in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl (as well as Roadside Picnic & Stalker the movie) that I find very compelling, one that deals with the concept of a fatal attraction. The various tales of stalking all deal with a common theme of people - smart people, good people - broken by their inability to resist something they know will ultimately destroy them. In a sense, stalkers - those poor fellows who find themselves unable to resist the life-or-death thrills of the Zone, not to mention the promise of riches and wishes fulfilled - are like the First Man: the Zone is just another incarnation of the damned apple in the Garden of Eden, and the stalkers are a latter-day Adam, surrounded by accessible riches, but unable to resist the damnation of grasping the one thing forbidden him.

In her forward to the newest edition to Roadside Picnic, Ursula Le Guin remarks that what separated this book from much of contemporary science fiction literature was its focus on the anti-hero: on the unremarkable downtrodden envied by no one. There are no Captain Kirks in the Zone - and the book makes it quite clear that those elitists who thought they could tame the Zone soon became it's first victims. Like the earth, the Zone belongs to the meek. Indeed, even the unofficial interpretation of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. acronym reads: Scavengers, Trespassers, Adventurers, Loners, Killers, Explorers, Robbers. To be a stalker is not exactly to be a prince amongst men.

|

| The poverty of stalking |

Roadside Picnic's stalker protagonist, Red Schuhart, is the perfect example: the man is little more than a petty thief and smuggler. Likewise, the stalker of the movie Stalker is of the same ilk, even his wife refers to him as a hard luck "bungler" (the inherent nature of "Strelok" from S.T.A.L.K.E.R.is unclear, though) . Heroes they are not.

Ultimately, Cassius' warning that the fault lies not in the stars but ourselves is just as suitable for stalkers as it is for any other addict. Stalkers are men given every opportunity to start afresh, to live normal, civilized lives, but they just cannot do it. Seemingly, most true stalkers would rather die chasing the mysteries of the Zone than abandon them for safe mediocrity (what Red refers to as "gloom and boredom."). The love for the "deadly bitch" cannot be given up, no matter the cost. And it costs. A lot. But on they stalk to their own doom.

This fatal attraction is perfectly expressed in Andrei Tarkovsky's movie Stalker. In the following scene, the stalker makes it quite clear why he has given up a decent life to tramp around the deadly Zone, his only "friend" in the world:

It is this sense of fatalism that really entrances me. In most other games, you are the Captain Kirk hero of the story, the guy who saves the day and avoids the peril. While it is true that you are a man of destiny in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl - it is a game, after all - this title nonetheless always seems to remind the player that he really is no different that the other stalkers in the Zone - he is just as vulnerable to its remorseless horrors. Indeed, even the ending of the game is something less than the hero saving the day, in fact it is downright...oblational (and that is the "better ending" of three). So even in 'victory', S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl reminds you that stalking has a price, and sometimes a high one at that.

I confess that this concept of stalking the Zone, of a fatal attraction, really hits the mark in the gamer in me. I have often thought that gamers are the world's only true stalkers. After all, it is only us that routinely put ourselves in (virtual) danger for the thrill of it; it is only us who can claim to have truly experienced the oft bizarre, otherworldly realms of gaming. Indeed, even the Writer's objection in the above vid hits home when he surmises that part of the thrill of stalking comes from playing God, from deciding who lives and who dies. Is this not part of the thrill of gaming? What gamer doesn't have a God complex? And while the stalker refutes this, even his defense of stalking sounds like the defense of a gamer: "my happiness, my freedom, my self-respect, it's all here." Yeah, that might be a bit too intense, but isn't gaming precisely about all of that? About happiness? About freedom? Even a bit about self-respect (why do you think so many games have 'leader boards')?

To stalk is to be an addict, it is to pursue a fantasy at the cost of everything else. Once again, something that reminds me of the modern world with its fruitless quest for utopia at any cost, with its message of "if it feels good, do it." It is to knowingly and willing take a leap into the abyss in an act of desperate solipsism.

Is there a better metaphor for the modern world?

Nice read. I had no idea that the Stalker game was loosely based on a book, good to know. Having just finished playing Metro Last Light I have this desire to read the book Metro 2033, but it also has me kind of wanting to play the couple of STALKER games that I've had for ages.

ReplyDeleteThanks! Stalker is a true classic. While I haven't played Last Light, I did get halfway through 2033 and loved it (I need to finish it once and for all). I was surprised at how it plays out like a spin-off from Stalker. I think the fellas knew that GSG wasn't long for the world and abandoned ship in an effort to keep the spirit of the franchise alive. I started to read the 2033 novel and really enjoyed it. Very good. I didn't get far because I put it down until I get a chance to play Last Light (or the Metro 2033 movie ever becomes reality - it was optioned two years ago).

ReplyDelete